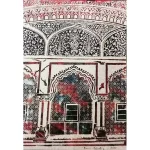

Handicrafts from India have attained a worldwide regard for beauty, ingenuity, artistry and as a medium for the expression of rural India. Pride of place is, however, inevitably given to Indian embroidery. Its infinite variety, delicate handwork, arrangement of form and colour make it pleasing and appealing to people the world over.

Although the origins of Indian embroidery are obscure, there is evidence that the craft was practiced in ancient times and references to it exist in the Vedas and in excavations at Mohenjo-daro. The famous Indus Valley civilization of c. 2300–1500 BCE revealed bronze needles. Megasthenes, ambassador to the court of Chandragupta Maurya in c. 300 BCE, made reference to Indian garments being “worked in gold and ornamented with semi-precious stones”. Famous are the vast embroidery karkhanas (workshops) started by the Mughal emperors where the influence of Persian motifs began to be apparent on indigenous designs. There are numerous references to exquisite workmanship of Indian embroidery by the early travellers to India from Germany, France, Holland and Portugal. The plaudits lavished upon Indian embroidery are probably because they captivate different tastes, and because of their sheer diversity in style, form and complexity. There are so many types steeped in their own history and tradition. The influences dominating each style related to the legends and fables, the climate and landscape and the social and economic factors of that region. Ultimately of course, the dreams and aspirations of the craftsman dominated the style.

More recently, the Sujanis or quilts of Bihar have directed the spotlight in their direction. The Sujanis, indeed all the quilts of India, have reached their epitome in the Kanthas of Bengal. ‘Kantha’ means rags, and in making Kantha disused bits of cloth are joined in a new context which gives the viewer an aura of change. The Kanthas were made by relatively prosperous middle-class women often as a dedication from daughter to father and wife to husband. After several layers of old saris and dhotis had been pieced together to the desired thickness, the embroiderer would start working the centre with the traditional lotus medallion. Then she would proceed outward depicting all manner of motives – animals, birds, flowers. Even items of everyday use such as a comb, nutcracker and hukkah were not considered too mundane.

The needle women used simple running of darning stitches which formed a pattern on both sides of the quilt. The coloured thread for the embroidery was laboriously unpicked from sari borders. After all the motifs had been worked, the intervening ground was tautly covered in white quilting giving these portions a rippled appearance.

The outstanding feature of the Kantha is its sophistication, manifested sometimes in the limited colour scheme, sometimes in the imaginative depth of the design and always in the standard of craftsmanship. Unlike the Chamba rumaals, the pattern in each instance is the work of the women who embroidered it —no painter traced the figures, they are not embroidered versions of pictorial designs. Because of this, there is very little repetition in the pattern of the Kanthas – each is a tribute to the needle woman’s originality.

Indian embroiderers could compare themselves with needle women from another clime. “My whole life is in it. All my joys and all my sorrows are stitched into that quilt. All the little pieces included 30 years of marriage, the rough and tumble with the boys and the precious hours with the girls.”

The Romans described embroidery as ‘Painting with a Needle’ – in India it has attained the level of high art.