I had the opportunity to meet Keshav Shankar Pillai, better known as Shankar, in 1986, soon after he turned the grand age of 84.

Shankar remembered with fondness the days of exciting encounters with nationalist leaders and dignitaries like Gandhiji, Nehru, Rajaji and Lord Linlithgow. His thoughts took him back to the memorable morning when the Hindustan Times carried “that horrid little cartoon of Lord Linlithgow, depicting him as the Goddess Kali astride a burning body in a graveyard that was India. When the phone rang and I heard the voice of the Viceroy’s military secretary, I thought, there goes my career”, he reminisced.

With his knees shaking, he answered the call and there was Lord Linlithgow himself on the line, his voice very friendly. “Shankar, my boy”, he said, “you have drawn a wonderful cartoon – you must send me the original immediately!”

Shankar made the cartoon an integral part of the newspaper and spared no one – slowly his victims became his biggest admirers and being ridiculed by Shankar became an honour. He is recognised in India as the doyen of cartoonists.

“I began drawing cartoons when I was a school boy, and later did some for a few Bombay journals. In 1930, one of my cartoons fetched five rupees which was quite a big sum in those days.” From Bombay, Shankar moved to Delhi and joined the Hindustan Times. There were no guidelines as such but one had to study political trends to analyse the implications (especially for the future) and reveal them through the cartoon for the common man to understand.

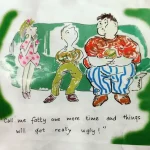

Shankar maintained that if cartoons did not cater to cheap sensationalism, they would be generally acceptable to everyone including politicians.

“My cartoons”, he said, “were devoid of malice to anyone. They were done with good intention and meant for pure humour. Compared to the welcome extended by the British rulers and their approbation of my cartoons, my experiences with the Viceroy’s Executive Council were not so encouraging.”

However, Panditji (Nehru) was an exception. Inaugurating Shankar’s Weekly in 1948, he said, “You may do whatever you like, but don’t spare me, Shankar.” Shankar’s Weekly, the Punch of India ran for 27 years. It coincided, but had nothing to do with, the Emergency. It was essentially a political journal which recorded events and even reported happenings in Parliament in its own inimitable way, tongue very much in cheek.

It was a journal of opinion, of positive dissent amidst a wave of moron-like conformism. Most of its copy came from non-professional writers all over the country. As the Indian Press said in September 1975: “It was just short of a free-for-all forum where one could have his say within the limits of decency and get away with it. James Thurber, it is said, mourned his times with laughter. Shankar’s Weekly had the last laugh at everything these 27 years and would not like an angel of sorrow over its grave; it died laughing.”

When Shankar put down the brush for the last time, almost a decade before I interviewed him, he did not do it to rest on his laurels, but to carry on a task which had become close to his heart, inculcating art and literature among children.

In his cramped room in the offices of Shankar’s Weekly on the third floor of a building in New Delhi’s crowded Connaught Circus, he mused, “why not leave the grown-ups to themselves for a while? Let me try to know children for a change. Children are beautiful, unspoilt, lovable. They deserve the best of everything.”

Shankar’s involvement with children started in 1949 when he brought out a special Children’s issue of the weekly. “I announced a competition for children in India and invited drawings, paintings and writings from them. Nearly 1,900 children sent in their entries and the best among them were awarded prizes and the results printed in the children’s issue.” In 1950, information about the competition was passed on to other countries and the second competition received 18,000 entries from nearly 17 countries. Shankar set up the Children’s Book Trust in 1957 which also runs the International Dolls Museum.

“The day I switched off cartooning,” he said, “I have never looked back.”