Among the numerous types of tribal and village woven containers of Iran, the tachehs are quite special. These large bags are made by the villagers of the province of Chahal Mahal, in the foothills of the Zagros mountains, west of Esfahan. The tacheh are used to store wheat, barley and flour. Their designs are very different from those of other types of village bags.

The tacheh of Chahal Mahal appeared in the Tehran bazaar for the first time in 1991 and caught the attention of Parviz Tanavoli. Their appearance caused some surprise, because though Chahal Mahal was well known, the tacheh were unknown outside their villages. “The word tacheh,” explained Parviz, in his book ‘The Tacheh of Chahar Mahal’, translated by Amin Neshati, “is a Persian word for tribal or rural containers. Ta or Tai in Persian is ‘bag’ or ‘bale’ and cheh means ‘small’, translating simply into ‘small bag’. In fact, research has shown that the word tache, which is of ancient Persian origin, has its Indo-European roots and could be akin to the German ‘tasche’ which also means a bag or sack.” Parviz says that in terms of novelty of patterns and designs, Chahar Mahal Bakhtiari is one of the richest centres of rug-weaving in Iran, so much so that this novelty can be felt from one village to the next, sometimes no more than a few kilometres apart.

I came across tacheh and learnt about its history when Darius Zandi, owner of the gallery Courtyard in Dubai, held an exhibition. He admitted that he was very happy to be part of perhaps the first display of Iranian culture and craft in the Emirates since time immemorial. “When I was in Tehran,” says Daruish, “I happened to see these tachehs and salt bags and could not resist planning an exhibition of them in Dubai. They are so unusual and considered very pious because the containers carry bread and salt, which are the most precious commodities of nomadic tribes.” Daruish also selected a number of kilims for display and sale at the exhibition.

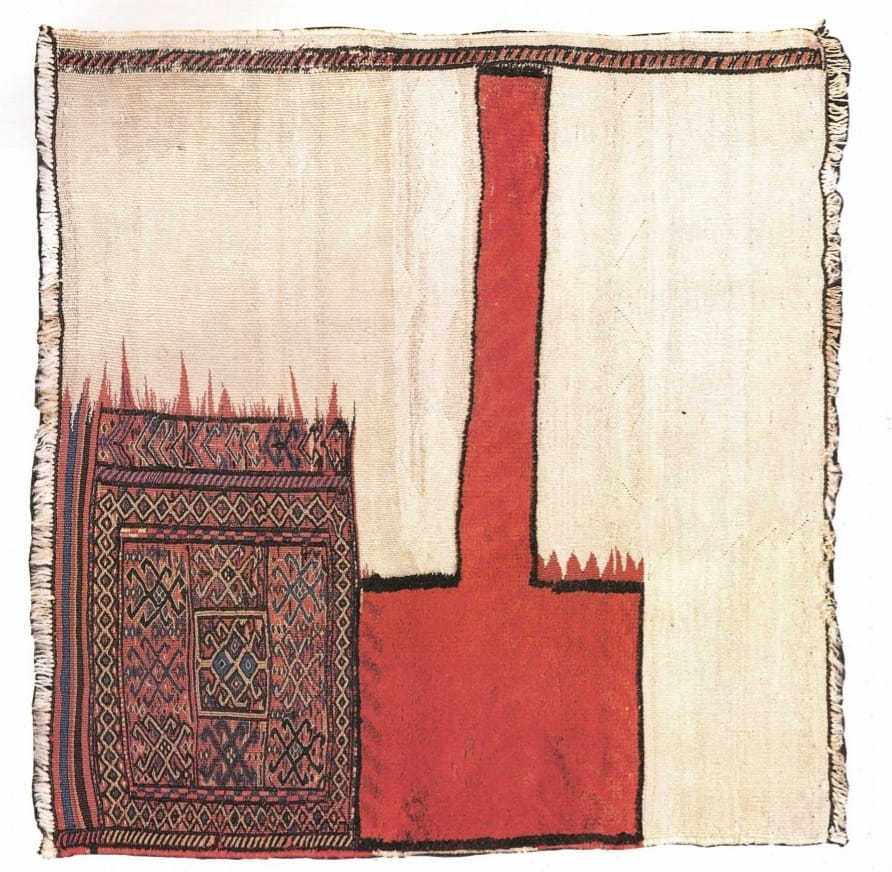

Farah Abougasemi, who helped Daruish to put the exhibition together, described the tacheh as a fairly large container, measuring 130 cms x 100 cms with an area of 1.30 square metres. Almost a fifth of the area is pile weave similar to a carpet with a warp and a weft, and the rest is often a basic weave which only goes in one direction. “The weaver has free play when he is making his tacheh because he almost always creates it for himself and his own use.”

“The use of cotton,” explained Parviz, “became more common among the Chahar Mahal weavers in the 20th Century. Usually woven in pairs, the tacheh resembles a small kilim which is cut and converted into two separate tachehs or folded and sewed down the middle to form a twin tacheh. Tachehs were also used to carry utensils on a horse and later hung in tents when nomads stopped for the night. Another interesting item is the ‘sofreh’ or the bread container. Bread was wrapped and carried in this cloth, and when it was time to eat, the cloth was spread with the bread in the middle and members of the tribe sat around it to eat.

Kilims or flat woven rugs without a knotted pile originated from Iran, Afghanistan, Ukraine, Syria, Lebanon, Turkey, Poland and Hungary among other places. “Kilims gave the nomadic tribes an identity,” explained Zandi, “they were used on the floor, walls of tents, houses, mosques, and were also used as animal covers and bags for family and personal use.”

These floor coverings have played a special role in the family as part of the dowry or so-called bride price. In their book, Persian Kilims, Alastair Hull and Nicholas Barnard explain that then, as now, the crucially important occasion of marriage involved much more than the union of two people. The girl, betrothed at an early age, became an instrument of liaison between families to the mutual commercial, financial and political benefit of all parties concerned.

Young girls learning with their mothers made their own dowry of kilims and textiles as a labour of love. Each piece embodies the inheritance of family tradition and tribal folklore. The position and status of a family were directly related to the quality and quantity of the bride’s dowry, and this explains to some extent why the kilim has in the past had so much effort, craftsmanship and creativity lavished upon it with no prospect of financial gain from the souq or bazaar.

“Kilims, tacheh and salt bags,” explained Zandi, “are handed down the generations in Iran. That is why it has been possible to revive dying art forms of the tacheh and salt bags. We can only hope that the people in the villages will attempt to go back to weaving these floor coverings. Times have changed and what took months by hand will be done in hours by a machine.” In this fast moving world, handicrafts need to be revived for what they are – an expression and creativity of an individual.

Interesting. I didn’t realize it was made in so many countries.

I met a gentleman recently who collects Persian carpets. Have shared this with him.

Great information. Indeed old creative traditions are worth preserving. In India too is a plethora of antiques were earlier sold in what were called ‘chor bazaar’. Now in recent times society, irrespective of class has become aware of the pricelessness of antiques and collectors’ pieces. I remember buying beautiful carved furniture from the chor bazaars and auction houses of Bombay(now Mumbai) and Calcutta(now Kolkata) respectively. Such outlets have now sell only regular second hand furniture. Values have transitioned from antique jewellery to antique anything. The Indian government has gotten wise too and has imposed a ban on exporting anything 100 years and older! But the realm of antiques still remains unregulated and unsupervised by the absence of a strict Authority, at least in India. So it’s a kind of free for trade area till you get caught trading 😂.