CHIKANKARI: Chikankari of Lucknow and Uttar Pradesh is believed to have been introduced by Nur Jahan, wife of Mughal Emperor Jehangir, and worked originally only with white thread on white muslin. One of the impressions it gives is of being patterned on fine lace. The most popular form of the craft has the threads cover the back of the cloth in herring-bone stitch to produce an opaque effect on the surface. Unlike other schools of Indian embroidery, Chikankari has always had a commercial base. Today, it is still a thriving industry in Lucknow.

TODA EMBROIDERY: The Todas, a pastoral tribe who inhabit the Nilgiris or Blue Mountains of Tamil Nadu, are believed by many to be of Greek origin. Toda women embroider the ‘poothkulli’ or long wrap worn Greek fashion by both men and women of the tribe. The base material, normally white in colour, is hand-woven in single width and the embroidery is done by counting of threads. At the end of the 9 yard long ‘poothkulli’, wide bands in red and black are woven. The women embroider in between these bands creating a striking ‘pallav’. Another feature is that the embroidery is worked on the wrong side of the cloth to produce a rich, embossed effect on the surface.

EMBROIDERY: The narrow winding lanes of old cities in northern India house workers of gold and silver embroidery. The ‘Zardoz’ school of Delhi and Agra employs Salna (twisted gold thread) and Sitara (gold sequences) against a velvet or silk background. Like so many crafts which came under Muslim influence, Zardozi is resplendent in floral motifs, while animal and human figures find virtually no representation. The matter drawn on thick paper is perforated and transferred to the cloth by rubbing chalk powder wrapped in fine muslin. The base with the pattern marked is then stretched on a frame of bamboos held off the floor by supports.

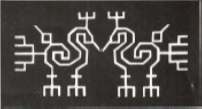

KASUTI OF KARNATAKA: Kasuti is a traditional form of folk embroidery practised in the State of Karnataka. The word is derived from ‘Kai’ meaning hand and ‘Suti’ meaning cotton. The craftsman here has no recourse to external aids like tracing the design and builds the motifs even as he is working the stitches. Four distinct stitches are used in the craft: the ‘gavnti’ or double running stitch, ‘murgai’ or zig-zag running stitch, ‘negi’ or ordinary running stitch and ‘menthi’ or cross stitch. Kasuti, which flourished in the Chalukya and Vijayanagar Kingdoms of the 15th and 16th centuries, is rich in symbolic motifs and patterns of court life and temple ceremonials including chariots, conchs, palanquins, lotuses and birds. Traditionally, the needlework is done by the women of the region for their personal use against handwoven sarees. ‘Irkali’ sarees, as they are called, are woven with 9 to 10 inches of wrap thread left loose at the ‘pallav’ or end. The craftsman uses these extra threads to work the embroidery. The colours for the work being taken from the base itself, the total effect when complete, though rich, is never bold.

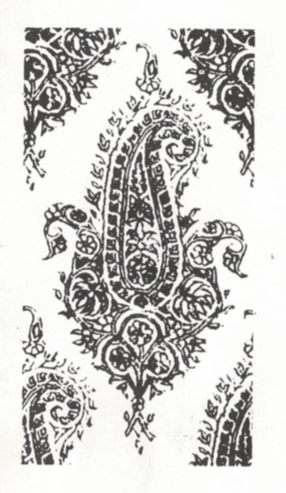

KASIDA OF KASHMIR: To a lover of Indian handicrafts, the Kasida embroidery of Kashmir needs no introduction. The embroidered shawls of this region have become a byword for exquisite craftsmanship the world over. All facets of Kashmir’s incomparable natural beauty – the cypress, the cone, the almond, the chinar leaf and lotus – find liberal representation in this craft. The embroidery worked only by men is an established industry. The base for the craft could range from silk and wool to cotton and leather. The design on perforated paper is transferred to the base by rubbing coal dust wrapped in muslin. The base material with the design marked is then handed over to the craftsman who uses different shades of cotton, woollen or silk threads to create the desired effect. Though Kashmir Kasida looks very complicated, the stitches themselves, including the darn, the chain and the satin, are unbelievably simple. It is almost as if the very splendour of the setting compels the stitches to recede to the background. Done with a single thread they give to the needle work when complete, a rather flat and formalised appearance.

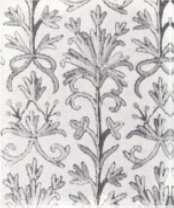

KASHMIR CREWEL: Traditionally, the crewel embroidery of Kashmir is worked on ‘namdas’ or woollen carpets. Nowadays, it is also done on thick yardage material which is popularly used for furnishing. The foundation of the craft is the chain stitch. Flowing floral and creeper designs are filled with rows of chain stitches rotating from the centre. The needle craft, done with a hook and woollen thread on a thick background, creates a rich embossed effect.

PHULKARI: Worked by the peasant women of Punjab, Phulkari ‘odhanis’ or shawls are intricately woven into the cultural life of the high-spirited and hard-working people of that region. They form an important part of the bridal dress, are given away as dowry and worn on all festive occasions. Even in death, a married woman’s bier is covered by a finely worked Phulkari. The base for the embroidery is handspun, handwoven khaddar, generally in shades of red. The unique feature of the craft is that it involves the use of only one stitch – the simple darn. The stitches are worked on the wrong side of the cloth with a silk thread called ‘pat’ in Punjabi to produce a smooth silken sheen on the surface. The predominant colours of white, yellow, orange, red, green and magenta are arranged to give a stunning kaleidoscopic effect.